Canada as seen through the Eyes of New Brunswick Editorial Cartoonists:

The Insight and Humour of Josh Beutel and Bill Hogan

Preface

Preface |

Introduction

Introduction |

Editorial Cartoon Database

Editorial Cartoon Database |

Classroom Activities

Classroom Activities

What is an editorial Cartoon and what is it supposed to do?

What is an editorial Cartoon and what is it supposed to do? Okay, so I’m looking at an editorial cartoon, what now?

Okay, so I’m looking at an editorial cartoon, what now? Editorial Cartoons in Canada

Editorial Cartoons in Canada Biographies

Biographies What are Archives?

What are Archives? Here are some links that will help you to research editorial cartoons

Here are some links that will help you to research editorial cartoonsArchives hold a broad range of material of interest to many people. Individual documents and groups of documents can also provide information and evidence on many different subjects in varying layers of detail. This combination makes for endless possibilities of how archival material can be used and means that several individuals may use the same document for different purposes, from the straight forward to the interpretive. One of the most interesting types of documents is the editorial cartoon. Like most archival material after the initial use for which it was created, it remains largely out of public view. Archives are attempting to increase the accessibility of their holdings through the internet and this site is designed to provide such availability to the editorial cartoons at the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick. It has been designed to utilize the varied potential uses of each item but allows you to choose the manner in which you access them. Archives have a direct potential use at all levels of education, from elementary school through life-long learning and one aim of this initiative is to facilitate the use of archival material for learning purposes, especially by students and teachers. Editorial cartoons have the extra advantage over many other archival sources of providing entertainment along with food for thought. We hope you enjoy this presentation and we welcome your feedback.

The Provincial Archives of New Brunswick is grateful for the financial support provided to create this resource through the Canadian Cultural Online Program of the Department of Canadian Heritage, and the cooperation and encouragement of the Library and Archives Canada and the Canadian Council of Archives.

What is an editorial Cartoon and what is it supposed to do?Editorial cartoons are depictions of objects, events, and people put together in such a way as to convey a message and encourage debate. To help support his or her point, the cartoonist will use humour, satire, caricature, and symbolism to say in just one panel what might otherwise take several pages of writing to get across. To this mix the cartoonist may also extrapolate or simplify to focus greater emphasis on elements of a story or to spark further discussion.

Cartoonists rarely portray issues and people in a positive light. Caricatures, in which the artist selects and exaggerates certain features of the subject, are usually not very flattering. This is partly because things that are grotesque and flawed are more humorous, and partly because the artist is providing his readers with an image that represents their frustrations with the way things are. In this way the cartoonist is speaking both to and for the reader.

Editorial cartoonists are responsible for commenting on things that concern their audience. This means that he or she has to take into account what the reader knows, where they are from, and what they would think is important. This is why provincial and federal politics and politicians are the most frequent subjects of editorial cartoons. More specific topics that you would find in editorial cartoons in Canada include language issues; our economic, political, and cultural relationship with the United States; historical ties to Great Britain and the monarchy; regional, provincial, and national unity; economic issues of taxation, inflation, and recession; and social issues of alcoholism, poverty, working conditions, human rights, and gender/race relations. Whenever you hear a big story on the news, you can bet you can find an editorial cartoon about it.

Okay, so I’m looking at an editorial cartoon, what now?Despite how simple or direct they may appear, editorial cartoons can be quite complex and subtle. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then an editorial cartoon is worth a book – or at least a really long essay. To fully understand what the cartoonist is trying to say, we have to identify and understand all of the elements of the cartoon.

The main visual elements of an editorial cartoon are people, objects, captions and quotes. However, identifying what these elements are is only the first step in understanding what the cartoonist is trying to say. You may think that who and what are in the cartoon, where they are, what they are saying, and what they are doing is all that you need to know to get whole picture. Although it is true that this is a crucial first step, it is important to remember that cartoonists have to use every tool at their disposal in order to make their ideas as complete as possible. The size and placement of people and objects, as well as facial expressions and physical appearance, are often clues to what the illustrator is trying to say. More importantly, these elements might represent something other than what they appear to be. Cartoonists often use

symbolism, which means substituting one thing to mean another. A good example of this would be using an image of Santa Claus as a symbol for the spirit of giving. It is therefore not only necessary to identify the elements of an editorial cartoon, but to interpret them.

As previously mentioned, cartoonists need to take into account what a reader knows; they therefore have to make

assumptions about their audience. This could mean taking some things for granted or having to include extra detail to bridge knowledge gaps. To do so, the cartoonist will often include references to every day life (like going to school, eating at restaurants, and mowing the lawn); popular culture (like television shows, advertisements, and celebrities); historical events and personages; and other visual material (like well-known art, books, and quotations). In including these elements in the cartoon, the cartoonist is assuming that the reader will recognize these references and therefore understand what he or she is trying to say.

This is where the issue of

context comes in. Context is the set of facts or circumstances that surround a situation or event and determines its meaning. The illustrator’s message might be completely lost if you do not have an idea about the time and the place in which his or her work was created. For instance, if you are talking to someone who is well-read but has never seen a television, and you say, “That guy is just like Homer”, she will probably think you are referring to the Greek poet and assume that this person is very wise and well-spoken, as opposed to the oafish, cartoon character Homer Simpson. Understanding such references is key to fully appreciating the cartoon. In examining an editorial cartoon, it is very important to have some understanding about the political, social, and cultural context in which it was created. If a cartoon was created in Saint John, New Brunswick, in July of 1978, you should at least be aware of the major events and important people associated with that time and place.

As the audience, your context is also important, for it is what gives you your

perspective. Your perspective shapes how you view and interpret the world. For instance, if you are coming from the perspective of a student, you might not approve of cuts to education system funding that would make you have to sit on the floor as opposed to on a chair or at a desk. From the perspective of a financial consultant, this might seem to be a smart move that would save the province millions of dollars that could go toward building better roads. Thus your perspective helps you to form opinions and make judgements about topics that might go against the intended message of the illustrator. Being aware of both your perspective and the perspective of the illustrator will go a long way in helping you to understand what is being said and why.

Once you have identified and interpreted all the elements of the editorial cartoon, keeping in mind your potential bias and the illustrator’s perspective, it is only one small step to figure out what the overall message of the cartoon is meant to be. Once you have that, you can choose to either agree or disagree with the cartoonist’s point, and you may want to think about and discuss this issue further. This, after all, is the objective of the editorial cartoon.

Synopsis:

- Editorial cartoons are depictions of objects, events, and people put together in such a way as to convey a message and encourage debate.

- Cartoonists use humour, satire, caricature, and symbolism to get their point across.

- Editorial cartoons speak to and for the audience.

- To analyze a political cartoon:

- Identify and list people, objects, captions and quotes.

- Note where things are placed and how people look – are they portrayed positively or negatively?

- Interpret the symbols and other visual and verbal clues.

- Investigate the time and place the cartoon was created.

- Identify the cartoonist’s perspective and overall message of the cartoon.

Editorial Cartoons in CanadaEditorial cartoons have been part of the Canadian political landscape since before there was a Canada. Many of the issues we see today were just as important at the beginning of our history, even though the people have changed. Although they had existed in one form or another for quite some time, editorial cartoons began to be published on a regular basis in Canada in the 1840’s in the publication Punch, on which many later publications were modeled. Canadian editorial cartooning as we would recognize it today really began to emerge in the 1870’s with John W. Bengough (1851-1923) and his publication, Grip, one of whose main subjects was Canada’s first Prime Minister, Sir John A. MacDonald. The cartooning trend soon began to grow in the mainstream media. Henri Julien became the first cartoonist to be hired full-time by a newspaper in 1888 when he began working for The Montreal Star.

A distinctive Canadian style did not really emerge until following the Second World War. New artists who broke out of the American-based cliché mode of cartooning were led by Robert Lapalme (1908-1997) at Le Devoir; Duncan Macpherson at the Toronto Star, Leonard Norris (1913-1997) at the Vancouver Sun and the Montreal Star's Ed McNally (1916-1971). It also became more common for editorial cartoons to not agree with the position of the publications in which they appeared.

As the art became more recognized, the profession was considered more legitimate. In 1949 the Canadian National Newspaper Awards introduced a category for editorial cartoonists and in 1963 an International Salon of Caricature and Cartoon was organized by Robert LaPalme in Montréal. More recently, The Association of Canadian Editorial Cartoonists was formed in the 1980's to encourage solidarity in the editorial cartooning community and to address common issues concerning this group of artists.

In recent decades, many editorial cartoonists say that they have experienced a “libel chill” in which they feel they have to censor themselves in order to avoid threats of lawsuits or losing their jobs. Due to the nature of their art - lampooning, criticizing, and often outright insulting powerful political figures, a backlash is sometimes inevitable. In 1979 a particularly well-publicized lawsuit against The Victoria Times newspaper and its cartoonist Robert Bierman by the BC Minister of Human Resources, William Vander Zalm, brought this into the public eye. Bierman’s cartoon, meant to criticize Vander Zalm’s policies, depicted him cruelly pulling the wings off flies. The judge ruled that the illustration was defamatory, and many cartoonists around the country produced their own version of the cartoon to protest the ruling. A Court of Appeal eventually reversed the trial court’s decision, as it considered the cartoon “fair comment”. Although the eventual outcome was what the cartoonists wanted, it introduced questions about the consequences, legal and otherwise, of freedom of expression.

BiographiesThe editorial cartoons you are about to view come from two different cartoonists, Josh Beutel and Bill Hogan. In order to help you understand their perspective, their biographies are included below.

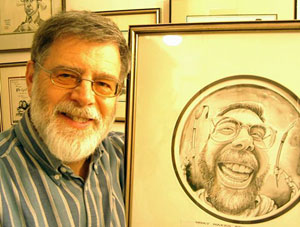

Josh Beutel

Josh Beutel was born in Montreal in 1945. He pursued degrees in Fine Arts and in Education, following which he taught high school Art classes in both Ontario and Labrador. He left teaching in 1972 to pursue his career in cartooning. Mr. Beutel moved to New Brunswick in 1976 and began to produce editorial cartoons on a contract and freelance basis for weekly and daily newspapers in the region. He later moved to Saint John from Sackville, NB to become the resident cartoonist for

The Telegraph Journal and

Evening Times-Globe from 1978 to 1993, and during much of this time his work also appeared in syndication. His work currently appears in the weekly publications

Here and the

Kings County Record and occasionally in the

Telegraph Journal. His cartoons have been published as well in

Newsweek, the

Financial Press Review, the

Globe and Mail and in other publications in the U.S. and Canada. He has participated in a variety of international cartoon exhibits in Brazil, Poland, the United States and Canada. He has produced 5 books of his cartoons, the last being

True (Blue) Grit: A Frank McKenna Review. In addition to the legacy of his cartoons, Beutel’s libel case over cartoons he created in response to anti-Semitism further strengthened the protection afforded editorial cartoonists.

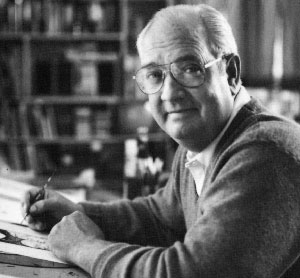

Bill Hogan

Bill Hogan was born in Montreal in 1939, the son of Miramichi natives William J. and Heloise (Lousier) Hogan. Bill moved with his family back to the Miramichi at the age of two and lived most of his life in Chatham (Miramichi), NB. During his schooling Hogan took lessons from Sister St. Mary Ovide at the St. Mary’s Convent. Following graduation from St. Thomas High School he became an insurance investigator. Health issues curtailed his work in the insurance field and he turned his life long interest in drawing into a new career. His first cartoon was published in 1976.

Bill Hogan’s work has been the subject of three publications and his cartoons have been exhibited in many parts of New Brunswick, Halifax, Vancouver, and St. Estève, France. In 1989 Hogan won the Atlantic Journalism Citation of Merit Award and during his career won awards from both the Atlantic and Canadian Community Newspaper Associations. He was a member of the Association of Canadian Editorial Cartoonists and the National Cartoonists Society. In addition to his work being featured in the Miramichi Leader and Moncton Times-Transcript, it also appeared in the Fredericton Daily Gleaner, Campbellton Tribune, and on the CBC. Bill Hogan passed away on November 15, 2001.

What are Archives?Archives are where historically significant documents in all their forms are kept. These are the types of things that historians look at to help them write books and articles, genealogists search to find ancestors, publishers and film producers peruse for illustrations, and individuals look up information about their house, community, and if you are old enough themselves.

The Provincial Archives are responsible for those items that are of historical importance to New Brunswick.

This includes newspapers, diaries, architectural drawings, maps, posters, letters, ledgers, and almost anything else you can think of that was created by people living in New Brunswick, even before it was actually a province!

The Archives doesn’t just store old things. To make them useful for researchers, a lot of people are involved in conserving, organizing, indexing, and preserving these things so they will still be in good condition and be available for people like you to look at both now and a long time from now.

Some of these items even get digitized and put on the internet so a lot more people can learn from them, just like we have done with these editorial cartoons!

Here are some links that will help you to research editorial cartoons

Association of Canadian Editorial Cartoonists

Association of Canadian Editorial Cartoonists

Canadian Encyclopedia

Canadian Encyclopedia

Decoding Political Cartoons

Decoding Political Cartoons

Begbie History contest example

Begbie History contest example