Introduction to Situation

In March 2020, New Brunswick experienced its first cases of COVID-19 and swiftly moved into lockdown.

Throughout the more than a year and a half of public restrictions and social distancing measures,

numerous buzzwords were integrated into everyday vocabularies and news briefings. Examples included ‘new

normal,’ ‘flatten the curve,’ ‘household bubbles,’ and ‘unprecedented.’ The latter, although

ubiquitous and true for many New Brunswickers’ experiences, was not wholly accurate. Over one hundred

years prior, the Spanish influenza had engulfed the province into a similar state of uncertainty.

As with COVID-19, New Brunswick citizens had never lived through anything comparable to the influenza

outbreak. This online exhibit shares the history of the Spanish influenza in New Brunswick through a

variety of documents housed at the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick.

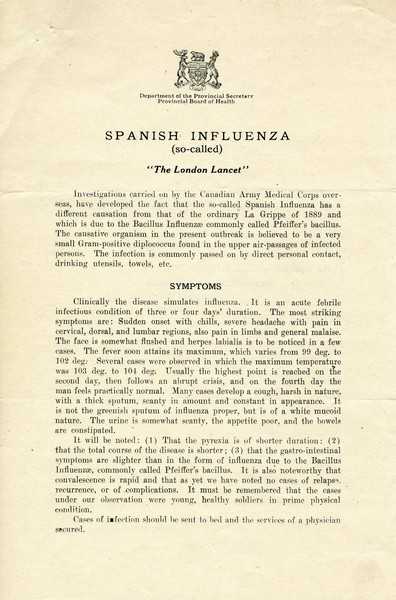

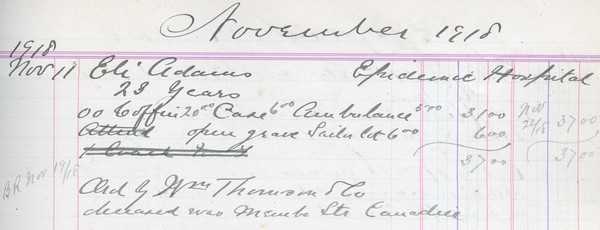

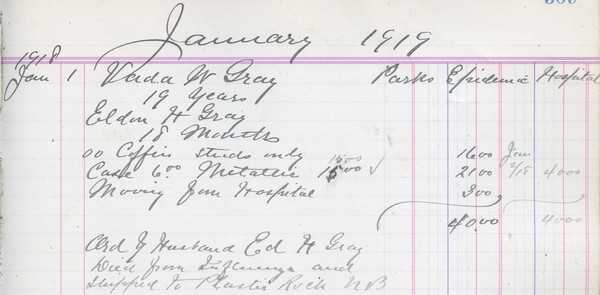

The Spanish influenza was an H1N1 virus that first affected soldiers during the spring of 1918. The second

wave came in the summer of 1918 when, thanks in part to these same soldiers, the virus achieved

an international reach. This 1918 wave was the worst, affecting mostly young people in their twenties or

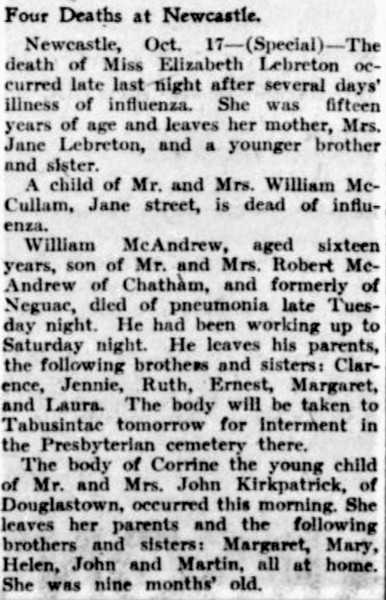

thirties (Lam and Lee, Flu Pandemic and You, 45-6; 59). New Brunswick was no exception and

suffered

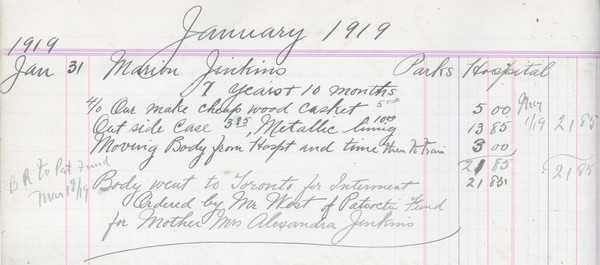

most during October and November 1918 (Jenkins, “Baptism of Fire,” 336). Between October 1918 and January

1919, the province experienced over 35,000 cases and 1,400 deaths (Jenkins, “Baptism of Fire,” 317).

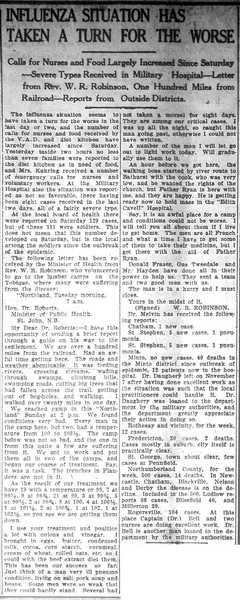

Soldiers landing in Montréal, Québec City, and Halifax ports were primarily responsible for carrying it

back home to New Brunswick. Likewise, sick military recruits from Boston travelled on trains to

training centres in Saint John and Sussex. Québec loggers were another source, spreading influenza in

lumber camps (Jenkins, “Baptism of Fire,” 331-2). In Canada, the disease hit the East first, before

it was brought westward through the railways (Jenkins, “Baptism of Fire,” 319). Although the province held

the second lowest death rate of the country, four deaths per one thousand, the pandemic still

rocked New Brunswick communities (Jenkins, “Baptism of Fire,” 318). The years 1919 and 1920 also saw two,

less severe, waves of the virus hit the province (Lam and Lee, Flu Pandemic and You, 59; 46).

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)