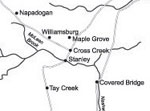

MAP: Northern York County, New Brunswick.

Daniel MacMillan was born on 22 March 1863, the first of seven children born to James and Margaret (née Robertson) MacMillan. His parents were Scottish immigrants from the Firth of Clyde and were among the first settlers in the small village of Williamsburg (part of the Parish of Stanley), which was founded in the early 1870s. Except for short periods of time when he went to work in the woods camps and lumber mills of York County, and one time when he went to Saskatchewan for the wheat harvest, MacMillan lived his entire life in Stanley Parish. He never married, which was unusual for a man of his generation. Like his parents he was a Presbyterian, active in church work and an elder of his Kirk by the start of the First World War. In politics, MacMillan was a Conservative and sometimes attended party conventions around election time. Although he attended school for only a few months, Daniel MacMillan was a highly intelligent and articulate person, and his diaries attest to his abilities as a writer. He died in June 1960 at 97 years of age.

When the First World War began in the summer of 1914, MacMillan was in the midst of a major transition in his life. Around the turn of the century he had taken over the running of the farm from his father. After 1908 Daniel assumed further responsibilities for the care of his father, who had suffered a stroke, and his brother Peter, who was mentally disabled since birth. His mother Margaret passed away in March 1911; Peter died in June 1914 and his father in July.

DANIEL MACMILLAN (1863-1960): Daniel MacMillan, a York County farmer and labourer, chronicled the hardships of rural working-class life in his diaries written between 1912 and 1928.

Most Canadians believed the war would be short and end in a glorious victory. Nobody in Canada or elsewhere could have foreseen the devastation and human suffering that would ultimately result. Daniel MacMillan fully participated in the war effort. Farmers in New Brunswick and elsewhere felt a solemn sense of duty to produce as much as possible. MacMillan, for example, donated 17 barrels of potatoes in December 1914 as part of the 100,000 barrels sent by provincial farmers in aid to war-torn Belgium. Throughout the war he also contributed money to a variety of initiatives undertaken in Stanley Parish, the majority organized by women's groups.

By the beginning of 1917, the Great War had been going on for more than two years and there was no end in sight. Gradually, the enthusiasm and sense of mission that had characterized the initial reaction to the war gave way to wariness. Hundreds of thousands of Canadian soldiers were fighting in Europe, and they were dying by the thousands. It was not clear that all of the effort and sacrifice would end in victory. Daniel MacMillan fully experienced the anxiety of the second half of the conflict. By the end of 1917, Jim MacMillan, a close nephew, and his own brother Charles had both gone overseas to fight. Indeed, Jim fought in and survived Vimy Ridge, where more than 3,600 Canadian soldiers were killed.

MACMILLAN FAMILY: Daniel MacMillan with Edith, his niece, and her children.

There were also mounting problems with the farm. MacMillan's farm was a modest mixed operation that produced a wide variety of grains, fruits, vegetables and animal and forest products, mostly for home consumption but also for sale. Like the majority of farmers in the province, MacMillan depended upon a delicate balance of favourable market and weather conditions. During those years when one or more phases of the operation experienced difficulties, he supplemented his income by taking employment in the forest industries of York County or cutting lumber on his own woodlot. Because of runaway inflation and a severe labour shortage, MacMillan experienced considerable difficulty in 1917. The diary entries for this year show a steady concern on his part for the future of the farm. He tried to maintain a positive outlook, but was forced to concede in December that he was “having a difficult time” . (For a selection of diary entries on this subject see “Having a Difficult Time” .)

Daniel MacMillan felt more relief than jubilation when the war finally ended in 1918. The war had taken a terrible emotional and financial toll on MacMillan and the people of Stanley, and the long-term effects of the conflict were already coming into view. More than a score of the 113 men and women from Stanley Parish who served in the armed forces lost their lives. Jim and Charles both sustained physical and psychological damage that they would carry with them for the rest of their days. In October 1919, MacMillan sold his farm, through the Soldier Settlement Board, to his brother Charles and wife Ella. His decision, in large part, was rooted in the wartime experience. In 1920, as Daniel MacMillan prepared to begin a new life as a labourer in the forest industries, the regional economy was sinking into a severe recession that would last until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.