HOT CARGO: These stickers and buttons were widely distributed among unions in Canada as part of the NO CANDU campaign.

In the early morning hours of 3 July 1979 a line of pickets assembled at the container terminal on the west side of Saint John harbour. Through the rolling fog, the pickets could see the shape of the Entre Rios II at dockside, a large freighter from Argentina that was waiting to load a $120 million cargo of heavy water. The picket line was organized by the Saint John and District Labour Council, and their message was spelled out on yellow buttons and signs reading “HOT CARGO” and “NO CANDU FOR ARGENTINA” .

The events that morning were the result of protests against Canadian exports of nuclear technology to Argentina, where a military coup in 1976 had overthrown the government after a bloody two-year civil war. The new dictatorship unleashed a campaign of repression against civil liberties and union rights, and the spectre of thousands of arrested, murdered and “disappeared” victims raised alarm among unions in other countries. In Canada a Group for the Defence of Civil Rights in Argentina, was formed by Argentinian exiles, and they rallied support from Canadian unions, churches and other groups. They called on the Canadian government for support. And in 1977 they started the “NO CANDU” campaign. For the Canadian government it was business as usual. A CANDU nuclear reactor had been sold to Argentina in 1973 – with big subsidies and secret pay-offs. Argentina still refused to sign the 1970 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty prohibiting the spread of nuclear weapons, but this was not a problem for Atomic Energy of Canada Limited. In 1979 they decided to make a bid for a second CANDU sale to Argentina that would be worth more than $1 billion.

There were protests against that sale on Parliament Hill in February 1979, but there was also a plan for more dramatic action. It was learned that in order to bring the first reactor online, heavy water from Chalk River, Ontario would soon be sent to Argentina. It was also learned that these supplies were likely to be shipped through the port of Saint John. At the request of the NO CANDU Committee, Saint John and District Labour Council President Larry Hanley arranged for Enrique Tabak, an expatriate Argentinian member of the coalition, to speak at the New Brunswick Federation of Labour meetings in May. Tabak received a standing ovation there, and delegates passed a resolution calling for the restoration of human, civil and union rights and the suspension of nuclear sales to Argentina.

With that the New Brunswick phase of the campaign was underway. The labour council in Saint John took charge, alerting local social action, church and environmental groups. By early June it was discovered that the heavy water containers had arrived in Saint John. Then it was learned that the Entre Rios II was expected on 1 July, with loading to commence two days later. “HOT CARGO” stickers began to appear around the city. Leaders of the NO CANDU Committee, including Tabak, arrived, pleased with the success of the labour council in mobilizing support.

On the morning of 3 July the stage was set for a confrontation on the waterfront. Larry Hanley and Barbara Hunter of the labour council arrived early, and they were soon joined by pickets from local unions, including the Canadian Paperworkers, the United Auto Workers, the International Association of Machinists, the Canadian Union of Postal Workers and the Canadian Union of Public Employees. There were also pickets from other parts of the province, including Barry Hould from the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway, Transport and General Workers in Moncton and Gilles Thériault from the Maritime Fishermen's Union. Church groups joined the line, as did representatives from the Voice of Women, the Conservation Council of New Brunswick, Project Ploughshares and the Maritime Energy Coalition.

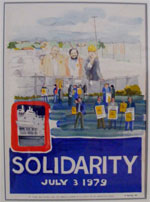

TO THOSE WHO HELPED: “TO THOSE WHO HELPED CLOSE THE HARBOUR * IN SUPPORT OF CIVIL RIGHTS FOR THE ARGENTINIAN PEOPLE” . This painting by Richard Peachey was presented to the Saint John and District Labour Council by the NO CANDU Committee in recognition of their solidarity with the workers of Argentina. The painting includes Jimmy Orr, Ronald McLeod, Larry Hanley, Harvey Watson, David Brown, Enrique Tabak and others. The painting is now on display at the W. Franklin Hatheway Labour Exhibit Centre, Rockwood Park, Saint John.

There was suspense in the early morning air as the first shift of longshoremen arrived for work. These workers had a strong union, with a long history of defending their own rights. Would it be work as usual under the provisions of their contract, or was this a day for a new level of solidarity?

The answer was not long in coming. When Hanley, Tabak and others started to speak, the longshoremen listened and took copies of their leaflets. Some walked away, while others joined the line, picking up signs and putting on buttons. Workers from the Brotherhood of Railway, Airline and Steamship Clerks, who were also arriving for work, also refused to cross the line.

At a news conference later that morning, Hanley explained the main demand of the protest: a suspension of nuclear sales to Argentina until human and union rights were restored and Argentina signed the Non-Proliferation Treaty. He also called for the release of 16 imprisoned union activists and the secretary to the Familiares de Detenidos y Desaparecidos por Razones Políticas (Relatives of the Detained-Disappeared) and for the Canadian government to accept 100 political prisoners. “We can't stop this shipment forever” , Hanley agreed, “but we can draw attention to both the violations of human rights in Argentina and the danger that Argentina may build a nuclear bomb” .

Meanwhile, Local 273 of the International Longshoremen's Association was facing a dilemma. The union's secretary treasurer and business agent stated that the work stoppage was illegal and that there could be fines and suspensions for violations of contract. But when the second shift arrived at 1 p.m., the longshoremen again refused to cross the line. The port remained closed, and no longshoremen reported for the start of the next shift at 7 p.m.

Telegrams of support poured in from across the country, and the protest also attracted the government's attention. The next day leaders of the NO CANDU Committee and their supporters, including John Simonds of the Canadian Labour Congress and John Foster of the United Church of Canada, met in Ottawa with the Secretary of State for External Affairs, Flora MacDonald. Before taking office in June 1979, she had spoken out against nuclear exports to countries such as Argentina. But on 4 July all she could say was that the matter would be dealt with by Prime Minister Joe Clark and the cabinet.

Meanwhile, two union representatives visited the Argentinian Embassy in Ottawa, and over the next weeks there was a response from Argentina. Of the 16 political prisoners identified in the protest, 11 were released, three were sent into exile and two were given prison sentences. One of the prisoners, steelworkers' leader Alberto Piccinini, was released a year later; when he visited Canada, he told Canadian workers that he understood the meaning of solidarity: “Unity is the unity of all of us; and it must go beyond national boundaries. I am very clear that I am free today because of the struggle first of the people in my country and second because of workers elsewhere – especially in this beautiful country” .

Although the first CANDU nuclear reactor in Argentina went into operation in 1983, the longshoremen had a second opportunity to protest Canadian policy. When Argentina ordered additional fuel rods in 1982, the Saint John longshoremen voted at a union meeting to refuse to handle the cargo. The supplies were then shipped by air from Montreal instead.

SOLIDARITY: Enrique Tabak (centre) of the NO CANDU campaign, with Saint John longshoremen Jimmy Orr (left) and Ronald McLeod (right) in Saint John harbour, 3 July 1979.

Meanwhile, in 1979 the sale of the second reactor had been stopped. In cabinet meetings Flora MacDonald continued to oppose the sales to Argentina. Her position was rejected, but when she addressed the United Nations in September 1979 she attacked Argentina for its repression of human rights and stated that it was Canada's policy to oppose the sale of nuclear technology to unstable regimes. It was a speech calculated to embarrass both Argentina and Canada, and, in MacDonald's words, “scuttled” the sale.

These events showed the importance of workers' solidarity within the global economy. They showed that, in responding to appeals for support, workers in one local community could have a far-reaching impact. In Saint John the longshoremen had given up a day's pay and come under criticism from the Maritime Employers Association, but their demonstration of solidarity had given them a place in history. Singer Nancy White wrote a popular song in their honour, with a rousing chorus, “No Hot Cargo for Argentina” , and a message of solidarity: “there's lines you just don't cross” .

These events have not been forgotten. Most recently, since the return of democracy in Argentina, the longshoremen of Saint John were nominated to receive the Orden de Mayo (Order of Merit), the country's highest honour for citizens of other countries. The proposal was supported by former Argentinians such as Enrique Tabak, who had appealed for support in New Brunswick in 1979. Jimmy Orr, one of the longshoremen who refused to cross the line that day, responded to the honour in these words: “All our members, and our members in the future, will be proud of it for the actions we did take on that particular day” .